Cézanne and the Revolution of Modern Art

Upper-right: Wheat Field with Cypresses (1889), Vincent van Gogh.

Lower-left: Montagne Sainte-Victoire (1904), Paul Cézanne.

Lower-right: Landscape with Two Figures (1908), Pablo Picasso.

Cézanne would never have interested me ... even if the apple he had painted had been ten times more beautiful. What interests us is the anxiety of Cézanne, the teaching of Cézanne, the anguish of Van Gogh, in short the inner drama of the man. The rest is false.

—Pablo Picasso

Born in an era of unprecedented technological advancement in photography such that personality is in turn exaggerated, we are fortunately endowed with the inborn advantage to perceive and appreciate the so-called “modern art” against the classicists of fine art who strived to depict the subjects “as they are”. I often find Claude Monet’s paintings appreciable even without contemplating the profound impact of Impressionism on later art forms. His ingenious usage of blue and purple to depict the shadow under the sun created a stunning symphony of colors on the canvas that is evocative of what we perceive with our own eyes. Nevertheless, Monet’s successors (not his followers, as they emerged as a reaction against Impressionists’ concern for the depiction of light and color), roughly gathered under the common title of Post-Impressionism, tilted towards abstraction and symbolism with their works becoming increasingly hard to appreciate without necessary elaboration on the topics and techniques. Serving as the indispensable transition towards modern art, the Post-Impressionist group encompassed many celebrated names, among which was Paul Cézanne, who was later widely regarded as “the father of modern art” with his profound influence extending to many renowned names including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Henri Matisse.

It might be hard to imagine that, when such a nowadays celebrated figure of Paul Cézanne died in October 1906 in Aix-en-Provence, the Paris newspapers reacted by publishing a handful of rather equivocal obituaries. “Imperfect talent,” “crude painting,” “an artist that never was,” “incapable of anything but sketches,” owing to “a congenital sight defect” — such were the epithets showered on the great artist during his lifetime and repeated at his graveside. It has not been long since the original derogatorily coined term of Impressionism finally gained its reception, but still, critics at that time did not reserve their sarcasm when confronting Cézanne’s works with such a revolutionary nature. Just like most of the revolutionists, his greatness was widely unrecognized by his contemporaries. However, the revolutionary experiments and techniques used by Cézanne in his art shocked the entire art circle and eventually became a principal driving force in the revolution of modern art.

It is never easy for someone to appreciate Cézanne’s work with pure instinct as we might have done when facing an Impressionism painting. Cézanne’s innovation requires careful examination to truly appreciate. Through one still-life painting The Basket of Apples () done in his mature period, one may get a glimpse of how Cézanne managed the whole painting. It is always beneficial to examine a reference from the 16th-century Dutch still-life paintings of the same motif. The one shown here is from Dutch master Willem Claesz. Heda (). It has to be admitted that when compared with the latter, Cézanne’s painting seems so tedious and dull, and may not look too promising at first sight. This painting has nothing more than its title has indicated: an ordinary basket of ordinary apples. The basket is so clumsily drawn that it seems to fall over soon. Where the Dutch master excelled in the rendering of soft and fluffy surfaces Cézanne gave us a patchwork of color dabs that made the napkin look as if it were made of tinfoil. The apples not tempting, the colors not fresh, and the contrast between dark and light so indistinct, this painting looks nothing compared to Heda’s still-life paintings which are incredibly lifelike with all intricate details carefully depicted. It was no wonder that Cézanne’s paintings were initially derided as “pathetic daubs”.

Right: Still Life with Gilt Goblet (1635), Willem Claesz. Heda.

“What is most straight seems like crookedness. The greatest skill seems like clumsiness. The greatest eloquence seems like stuttering.” (Tao Te Ching, Ch. 45). The old Chinese quote fits perfectly with Cézanne’s painting. Contrary to what we have perceived at the first sight, the paintings and the art system he developed were in fact full of complexity. Cézanne’s ingeniousness lay in his way to convert the seemingly “clumsiness” in his work into propulsion of the revolution of modern art. Back in the late 19th century, during a time when the art world was seemingly thriving and flourishing, the Classicism artists were able to paint objects with such realism and precision that with complacency they were unaware of the upcoming revolution. Art’s problems, as in every natural science, are never-ending. With the invention of perspective, the introduction of new painting material, and the improvements in drawing techniques like Chiaroscuro (the use of strong contrasts between light and dark), the problem throughout the history of human history to paint things “lifelike” seemed to be solved as early as 17th century. However, the invention of photography in the 1820s suddenly brought new challenges to the artists. Since then, humankind has had a better way to capture reality, more precise and convenient than any painter could. Cézanne and other artists of his time were forced to introspect and scrutinize the meaning of art that constantly changed and developed over time. When first appeared in human history more than ten thousand years ago, the function of painting was to record things that happened. With the development of human society and the emergence of religions, painting became affiliated with them, functioning as a tool to preach and instruct believers. Since the Renaissance, painters pursued to draw objects “as they are”. So, what were the meanings of painting in such a new period with photography? Cézanne’s work gave an answer to this problem with a far-reaching influence on art today.

Back to the painting, one thing that surely puzzles the viewers is the disjointed perspective, a mistake that even a beginner in the painting would be able to avoid. The right side of the table is not in the same plane as the left side, as if the two sides of the painting were completed using two different points of view. The edge of the table is slightly tilted from the horizontal. Similarly, the bottle on the table is tilted vertically as if someone had shoved the painting just before its completion. The basket slants in the opposite direction. The apples are rolling out of the basket and seem to be soon falling off the table. Painted with solid brushstrokes, the colors seem to be flowing on them. The oblique composition creates such a dynamic atmosphere that everything in the painting seems to be in motion. Cézanne incisively captured this fleeting moment and depicted it with such grandeur that it was unprecedented and revolutionary. In his experiments to unveil the meanings of paintings and art, Cézanne was prepared to sacrifice the conventional “correctness” of paint if necessary. He did not distort nature on purpose, but he also did not mind very much if it became distorted in some minor detail provided this helped him to obtain the desired effect, which, for this painting, is the subtle balance of the composition. The “linear perspective” did not interest Cézanne overmuch, so he would throw it overboard when he found it hamper him in his work. The Dutch masters painted their still lifes to show their stupendous virtuosity, whereas Cézanne chose this motif to study the problems confronting the entire art circle at that time.

It shall be pointed out that these changes in Cézanne’s art style were not done overnight, nor was he the first to delve into the meanings of painting. The Impressionists, as the very first trailblazer, explored the color reflexes and experimented with the effect of loose brushwork aiming at creating an even more perfect illusion of the visual impression. However, though the Impressionists defied many conventional rules of painting taught in art academies, they essentially shared a similar goal as the classicism master to accurately depict nature as it appears to human eyes. The disagreement between them was not so much about the aim, but rather the means by which it could be achieved. Despite its limitation, Impressionism played a crucial part in the formation of Cézanne’s art style. In April 1866, the 22-year-old Cézanne, the son of a wealthy banker left his hometown Aix-en-Provence for Paris, where he met the most radical artists at that time. Among them was Camille Pissarro, one of the leading figures in the Impressionism movement, who became a good friend and mentor of Cézanne after the latter settled in Pontoise in 1872. Though the strivings of Cézanne and Pissarro were in many ways dissimilar, Cézanne willingly listened to Pissarro’s advice, especially since this mild and patient man had an exceptional gift as a teacher. It was perhaps the only period of tutelage in Cézanne’s life, which greatly inspired him, yet at the same time brought him a dilemma. He had either to accept Impressionism with all its wild play of interacting color reflections and shimmering mist of the light and air medium, or he must reject it.

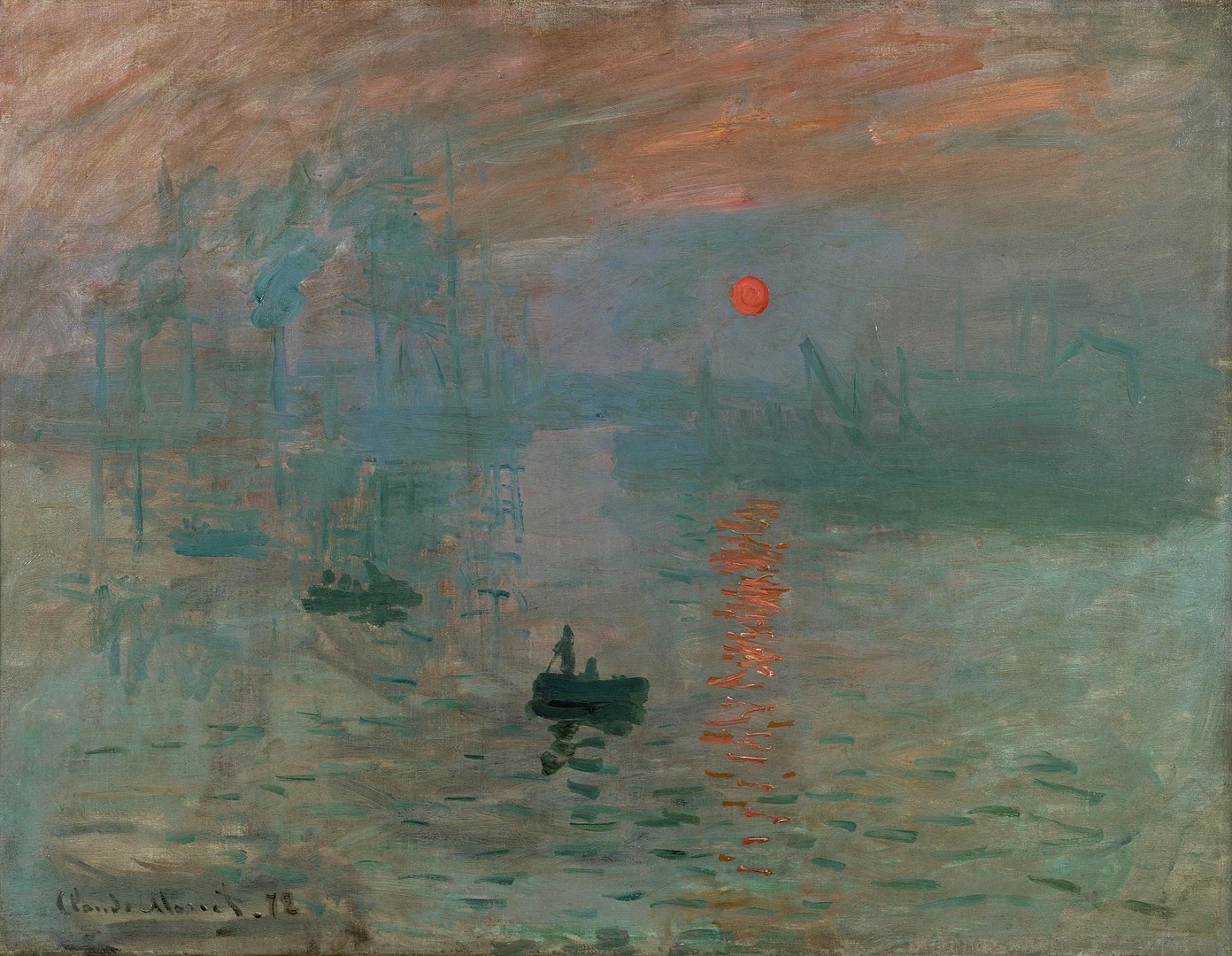

Cézanne chose to reject it and pursued his own goals. Perhaps the early-year friendship with the later renowned novelist Émile Zola has endowed this timid man with an inner perseverance for the things he pursued. Throughout human history, doubting the already-existing rules has always been a difficult and risky endeavor. It takes a brave and bold mind to challenge the established norms and expectations of their time, and even more so to attempt to create entirely new rules and ways of thinking. Cézanne was this daring man who would devote his whole life to painting and even give up the wealthy life of a banker. For more than a score of years Cézanne lived his life in solitude and loneliness, a life almost of a hermit, away from the hustle and bustle of the big cities, but also away from the reputation he should have deserved, just to study and experiment with the problems in the art. Only a great mind as Cézanne would regard money and fame as dirt. If the Impressionists took the first tentative step from classical art, Cézanne took another sturdy stride further. Though deeply influenced by Impressionism, Cézanne only partially adopted the outlook of the core Impressionists, forming his own style. From two paintings, Great Pine near Aix by Cézanne (), a landscape painting created during his mature period, and Impression, Sunrise, a renowned masterpiece by Impressionist painter Claude Monet () from which the term “Impressionism” originated, we can get a glimpse into the connection as well as the difference between Cézanne and the Impressionists in terms of the techniques of expression in their paintings.

Right: Impression, Sunrise (1872), Claude Monet.

Though depicting different motifs, it is not difficult to discern the similarity in the brushwork of the two paintings. The short, thick, and heavy brushstrokes on the canvas known as impasto, the discrete blocks of colors without much mixing — these techniques of Impressionists were adopted by Cézanne. The major difference lies in the way these two masters of art maneuvered their brushwork on the canvas. Cézanne’s brushstrokes were particularly distinct and bold, with vertical brushstrokes taking up the majority of the painting in concert with the sturdy and powerful trunk which is the center of the whole painting. Different kinds of green tangle and overlap, creating a feeling of strength and resilience of the great pine tree. On the other hand, Monet’s brushstrokes were more subtle as if carefully designed, creating a hazy and obscure scene of the sunrise, leaving the freedom of imagination to the viewers. The colors, tone, and texture are delicately balanced in this painting, showing Monet’s mastery of using light and shadow. This difference can be attributed to the different goals Cézanne and the Impressionists pursued. An Impressionist seeks to capture the fleeting quality of light, thus ignoring most of the details. We can distinguish vaguely the profile of the harbor in Monet’s painting and the figure in the small boat on the river. The rising sun and the beams of sunlight reflected from the rippling river seemed to wake the city from a dream. Monet ingeniously and subtly captured this moment. In contrast, Cézanne emphasized shapes and the depth of field which the Impressionists lacked. In his painting, the great pine tree is bathed in sunlight and yet standing firmly and solidly. The land and the houses seen from the gaps of branches and leaves present a lucid pattern and yet give a great impression of depth and layering. This landscape painting reflects what Cézanne had pursued throughout his whole art career — the balance and solidity of a classical master such as Nicolas Poussin had achieved, except that the latter appealed to the audience with a stage-like presentation of figures whereas Cézanne structurally ordered whatever he perceived into simple forms and color planes.

It is better to understand this difference using Cézanne‘s own words. As he once claimed, art is “a harmony running parallel to nature,” but not an imitation of nature. He said, “When I judge art, I take my painting and put it next to a God-made object like a tree or flower. If it clashes, it is not art.” As Cézanne believed, “Nature reveals herself to me in very complex forms”. The still-life drawing in The Basket of Apples provides a perfect example in which he tried to deal with the complexities of visual perception and the tension between stability and imbalance. In Great Pine near Aix, he tried to attain a sense of order and solemnness to restore the classical glory. Through all experiments, Cézanne strove to achieve his ultimate goal — in his own much-quoted words — “to make of Impressionism something solid and enduring, like the art of the museums”. Compared with such calm masterpieces with a solidified, almost architectural style of painting, the works of the Impressionists often look like playful and witty improvisations of colors and light.

Cézanne was not the only man who tried to deal with these problems of art, yet his approaches to solving them were unique and incomparable. Among his contemporary Post-Impressionism painters, many sparkled in the history of art with their own perception of art. Vincent van Gogh took drawing as a tool to express his inner emotions and sentiments, with his paintings full of fantastic illusions of swirls as his agonized inner self-portrayal (). Paul Gauguin, who was tired of Western society and exiled himself to the “South Sea Islands” Tahiti in search of simple life, focused more on the paintings’ function as an introspect of human society (). Comparing these strong personalities, we are able to say that Cézanne focused more on art itself. The Large Bathers (), often considered one of his finest works, presents the nude figures with such timeless grandeur that they seem to be “sliced out of mountain rock.” The memorable phrase comes from the great English sculptor Henry Moore who first saw the painting in 1922 when he was a student. The painting, serene and exalted in feeling, beautiful and subtle in brushwork, is wonderfully harmonized with the figures, the trees, the ground, and the sky seeming to blend together into one mysterious substance. Simplifications of shapes can be observed in these figures. Though the colors on the canvas seem alive with vibrant touches, the whole composition still possesses a feeling of stability. It was a miracle that Cézanne succeeded in reconciling the subjective impression and objective authenticity — the two seemingly contradictory goals. This concern with the overall feel and balance of the picture was at the heart of Cézanne’s great legacy to modern art.

Right: Houses at l'Estaque (1908), Georges Braque.

The influence of Cézanne’s revolution can never be overestimated. The way Cézanne simplified objects into geometric forms of “the cylinder, the sphere, the cone” has inspired many artists, lending credence to his position as one of the most influential artists of the 19th century. Among them was a young artist named Pablo Picasso who later developed Cubism and became one of the most eminent figures in the movement of modernism. At the early stage of Cubism (or “Proto-Cubism”), this reference from Cézanne was even more obvious with the easy-to-perceive visual similarity. Houses at l’Estaque, the painting drawn by Georges Braque (), is a typical Proto-Cubism painting which was ridiculed by critics as being composed of cubes and led to the term “Cubism”. The painting consists of a Cézannian tree similar to the one in and houses depicted in the absence of any unifying perspective, the technique Cézanne experimented in . Moreover, both Henri Matisse, the founder of Fauvism, and Pablo Picasso have remarked that Cézanne “is the father of us all”. Indeed, were it not for Cézanne’s brave experiments and innovation in the way we observe nature, the avant-garde would have taken much longer to push modernism under the public view. However radical these movements may seem at the first sight, they were actually consistent attempts to escape from a deadlock in which artists found themselves, paving the way for a new era of artistic expression and creativity.

Over the past century, Cézanne’s paintings have continued to captivate and inspire modern audiences despite the rapid evolution of art forms and the increasingly hypercritical taste. This enduring appeal is a testament to the greatness of Cézanne and his revolutionary impact on the art world. Through decades of experiments and attempts, the art forms we see today, installation art, conceptual art, and performance art, with Dadaism, Minimalism, Futurism, and many other isms, are indeed eccentric and confusing in terms of their appellations, not to mention their connotations. Some believe that this trend of eccentricity signals the demise of modern art. But it is truly the case? A hundred years ago, Paul Cézanne already gave his negative answer. The history of art is one of constant evolution and reinvention, just as an old Chinese saying goes, “In the Yangtze River, the waves behind drive on those ahead”. The road of art is never-ending; it always awaits artists to explore, and the brave as Cézanne will lead the way. It is perhaps the most significant enlightenment Cézanne and his revolution have passed to us, and surely will it be passed down from generation to generation.

Acknowledgments

I would also like to extend my sincere gratitude to Professor Qingsheng Zhu whose lecture History of Art greatly inspired me, and to Professor Ya Xu whose lecture on analytical writing helped a lot with my previous work upon which this post is built.

References

: National Gallery, London; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia; Musée Picasso, Paris. : Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago; Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. : Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg; Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. : Museum of Modern Art, New York. : Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. : Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia; Lille Métropole Museum of Modern, Contemporary and Outsider Art, Villeneuve d'Ascq.